The Tory Party Leadership Contenders’ Outrageous Historical Revisionism

Alan Lester

Conservative leadership contenders often say outrageous things as they vie for the support of the ‘Tory “selectorate’. Kemi Badenoch appreciated quickly that adopting an outraged blocking stance on a conversation about looming Commonwealth reparations claims was attractive to the party faithful. She got off the starting blocks in May, promoting the absurd notion that Britain had never profited from slavery. Compensating for a later start, Robert Jenrick has pushed the historical revisionism further, using the Daily Mail’s platform to suggest that those on the receiving end of slavery and colonial exploitation should thank Britain for it. He seems to be calculating that complaining that the victims of a crime against humanity aren’t more grateful to the perpetrators might prove yet more appealing to the Conservative membership.

Jenrick’s intervention is a breathtaking piece of doublethink. He accuses “leftist, pseudo-Marxist” academics of assuming “that modern western values were somehow universal 400 years ago” and of judging the past by these “impossible” standards. The allegation is pure projection. Before pausing for another sentence, he is off casting his own moral judgement on British colonialism. Unsurprisingly, it’s a positive one.

You may have thought that the very definition of colonisation – the rule, occupation and exploitation of other territories and people – would pose certain problems of retrospective moral justification. But Jenrick is as adept as Vladimir Putin in dismissing any such qualms. Colonisation was fine because “The territories colonised by our Empire were not advanced democracies. Many had been cruel, slave-trading powers.”

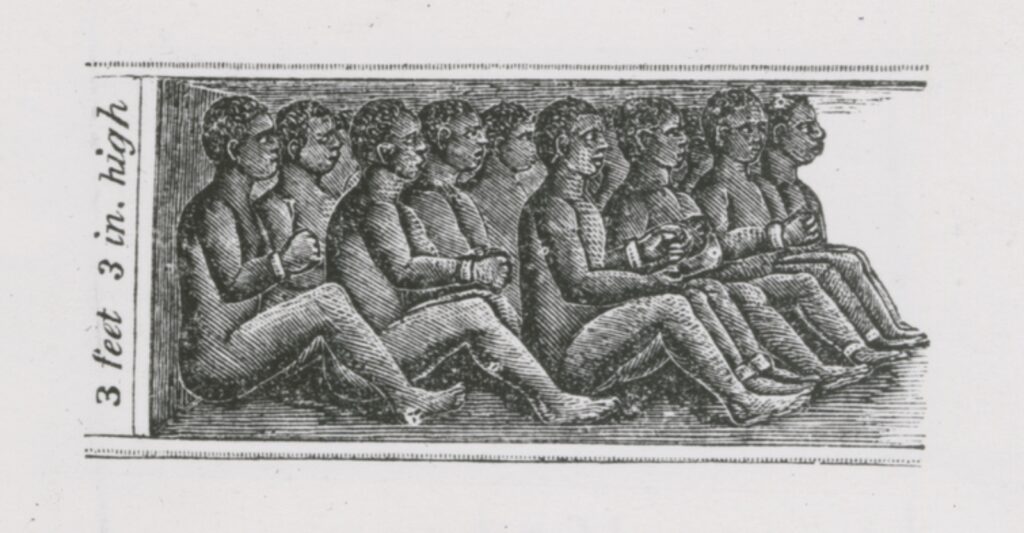

Never mind that colonising Britain was not an advanced democracy either. As the House of Parliament’s official history of the franchise notes, “Until relatively recently in British history the extension of the vote to all men, let alone women, was actively opposed by many who thought the vote should be restricted to those of influence and means. Professor Robert Blackburn noted that: ‘Even in the nineteenth century the idea of democracy, in the sense of equal political rights and universal suffrage, was still regarded by most as a dangerous experiment and subversive to any sound system of government’”. And who cares if Britain was also the dominant “cruel, slave-trading power” of the eighteenth century, trafficking more captives across the Atlantic between 1740 and 1807 than any other nation (3.1 million in all). The justifications simply pour out of him: “The British Empire broke the long chain of violent tyranny as we came to introduce … Christian values … we initially continued the barbarism of slavery. But – confronted by its cruelty – we ended it”.

Jenrick’s problem isn’t that “woke” academics moralise about the past. We just research and teach what happened and why. It is that the evidence we supply about colonialism interferes with his own desperate attempt to cast colonialism as a moral virtue.

Reasons to be Grateful?

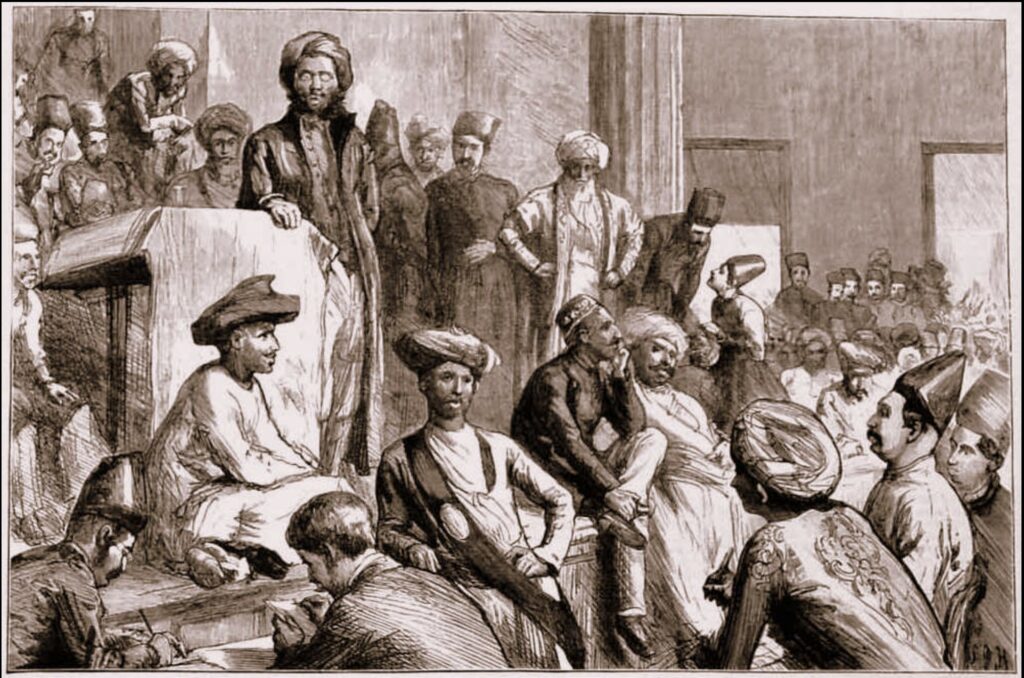

“We should be proud of the Empire’s achievements” assert Jenrick, Badenoch, and indeed all the populist Right commentariat. And the greatest of these achievements is apparently the rule of law. “Walk into almost any courtroom across the Commonwealth and you could be back in the UK”, Jenrick enthuses. Things looked a little different to most of the British Empire’s subjects. When Black and Brown subjects walked into colonial courts, the scales of justice tilted against them by White judges and juries. In India local people were trusted to participate in the lower levels of the judiciary more than in any other colony. But when White colonists there were told to accept the authority of Indian judges in 1883, all hell broke loose. The measure to remove racial discrimination, known as the Ilbert Bill, had to be rowed back so that White defendants could insist on at least half their jury also being White.

Meeting in the Bombay Town Hall in support of the Ilbert Bill, The Graphic, 25 January 1884

Britain’s ‘colour blind law’ was even more of a mockery in the other colonies. White colonists who beat or raped Black and Brown colonial subjects were rarely if ever prosecuted and tended to be acquitted by White juries. Black and Brown subjects who struck, disobeyed or were even ‘cheeky’ to White people were consistently and severely punished. When colonial governments needed to use more extreme violence to uphold White minority rule in the face of frequent protest and rebellion, they simply declared martial law. There are two basic facts that imperial apologists never seem to grasp: law in Britain and law in its colonies were not the same thing. What Britons said about the universal rule of law was not what they practised in their colonies.

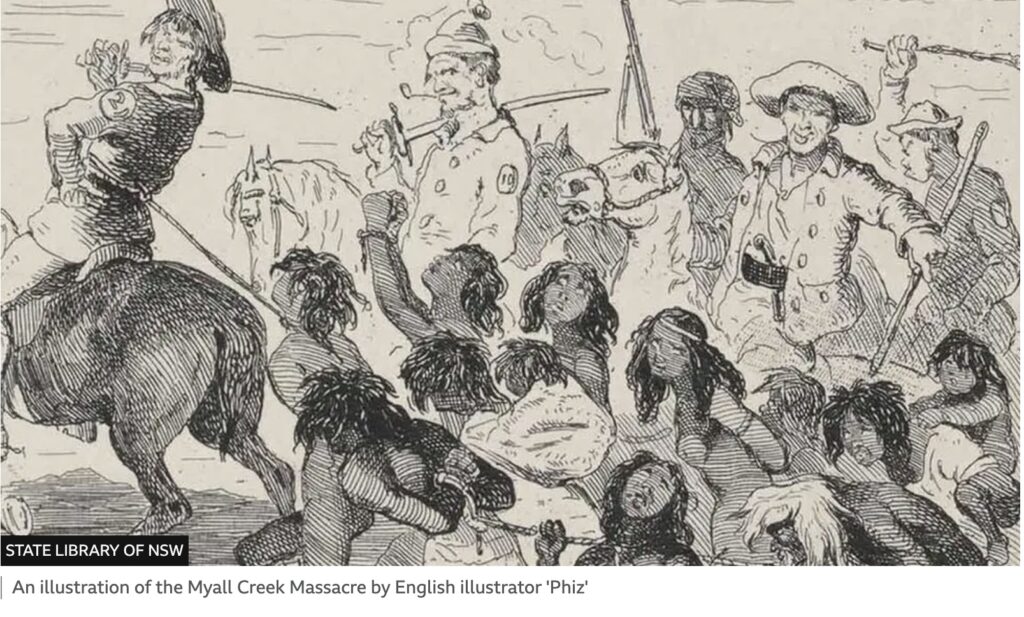

Jenrick’s second appeal for gratitude is based on the claim that the “British system of governance was the best in the world for promoting peace and prosperity”. He seems completely oblivious to the way that governance was spread. The coming of the British was the direct opposite of peace and prosperity for those subjected to colonial wars of conquest, which took place in nearly every year of the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

Millions of Native Americans, Aboriginal people, Māori, Africans, Afghans, Chinese, Indonesians, Malays, Pacific Islanders, Indians and Arabs were killed as Britons expanded their Empire through brute force. In 1886 the artillery officer Colonel Charles Edward Callwell, wrote a treatise on ‘small wars’ against ‘savages’, which became the British Army’s colonial field guide. It advocated ‘rigorous treatment … meted out to the enemy in crushing out disaffection’. Callwell explained that ‘uncivilized races attribute leniency to timidity … fanatics and savages … must be thoroughly brought to book and cowed or they will rise again’. Scorched Earth tactics – attacks on civilians’ homes, livestock and crops – were de rigueur in British colonial campaigns.

Once established the British Empire certainly obtained ‘prosperity’ for some: most notably Britons investing in colonial wealth extraction. Recent research on the Atlantic system of slavery has shown not only that Britain’s ‘key manufacturing regions of the industrial revolution’ relied on capital and credit generated from the trans-Atlantic slave plantation system, but also that ‘plantation investment and shipping … brought innovation in the mortgage and insurance markets, in multiplex financial transfers and in the expansion of commercial credit that linked provincial merchants, manufacturers and banks with the resources of the London money market’.

Indian merchants, landlords and aristocrats all benefitted from the security of British rule, its access to overseas markets and the opportunity to populate the lower ranks of its civil service and judiciary. Beyond India too, Black and Brown elites were accommodated into the governing and economic frameworks of Empire as junior partners to British rulers and investors. So there is some basis for Jenrick’s claim that imperial rule brought ‘peace and prosperity’ to some of its disenfranchised subjects.

But it was Britons who gained most from accessing ‘the surplus-producing and taxable capacity’ of the Indian and other colonised masses. British rulers could charge Indians rent and use it to buy their produce. Indian farmers and manufacturers were effectively paying British rulers to take what they produced. The British could then sell that produce, mainly cotton, opium and textiles, overseas, retaining the profit. In 1840 Montgomery Martin estimated the overall flow of capital from India to Britain between 1803 and 1833 alone at £724 million, noting that such ‘a drain even on England would soon impoverish her’. In 1884, the statistician Richard Temple estimated that of the £203 million at the disposal of the British state for general government within the United Kingdom, £89 million came from the UK itself (including Ireland), £74 million from India, and £40 million from territories and colonies in the rest of empire.

One effect of this extraction was the exacerbation of the famines that occurred under British rule. Starvation set in more readily during environmental crises as poorer farmers struggled to pay the rent required by their foreign rulers at the same time as feeding themselves, and as British rulers saw the provision of relief as rewarding idleness. Tens of millions died in famines under British governance before reforms began to mitigate them in the later nineteenth century. Three million more died in 1943, in part due to British wartime distractions and policies.

Jenrick should also try telling Australian Aboriginal people and Canadian First Nations that British colonisation brought them peace and prosperity. They are still living with the consequences of land dispossession, stolen generations and Residential Schools that amounted to a cultural genocide. He might also like to see if the majority of Black South Africans are grateful for the series of wars launched in the late 1870s to dispossess them of their lands, confine them into reserves and extract their labour for White-owned diamond mines, a series of interventions that laid the groundwork for apartheid.

De Beers Mining Compound, Kimberley, South Africa

It is not just that Jenrick and other apologists for colonialism hide the truth. They actively pump out disinformation. Mostly this is about Britain’s desire to do good “not only for ourselves, but for the world”, as Jenrick puts it. Having been a minor refrain in imperial apologias a few years ago, the idea that Britain made great sacrifices to end global slavery in particular is now a major refrain. Jenrick repeats a “statistic” that has been used as a weapon against a reparations conversation ever since the Daily Mail printed it earlier this year: “Ending the [slave] trade cost an estimated 1.8 per cent of our GDP between 1808 and 1867 – over twice what we spend on overseas aid today.” It is not true. It is one of five main disinformation strategies repeated ad infinitum in the media. More on that here. And more on the myths peddled to block a reparations conversation in particular here.

Robert Neeves

Thanks Alan. Brilliant if only people could face the truth about are past how much better a country we would be.