Alan Lester*

In recent months the Daily Mail and right wing groups have mounted a clamour for a new memorial to be built in Portsmouth. In principle, the proposal seems reasonable, since it is to commemorate a British antislavery initiative. However, given its motivations, the way that it has been promoted and its proposed design, this particular memorial campaign has attracted considerable opposition. In this blog I examine the case for and against it, concluding that the project is an exercise in White virtue signalling, historical falsification and the denial of racism.

Four months after Black Lives Matter protestors drowned the statue of slave trader Edward Colston in Bristol’s harbour, the conservative historian Jeremy Black wrote a piece in The Critic highlighting the exploits of the Royal Navy’s antislavery activities. The Critic describes its purpose as pushing back ‘against a self-regarding and dangerous consensus that finds critical voices troubling, triggering, insensitive and disrespectful’. Black found the critical voices of Black Lives Matter troubling, triggering and disrespectful and decided to defend the consensus instead. ‘Why does’ the slave trade, ‘this dramatic long-forgotten aspect of our history matter so much?’, he wrote.

… [D]espite all the criticism seemingly endlessly repeated today, we actually have many, many reasons to be proud of our history and of what ends we used our power to purpose. Notably so in our leading role in ending first the international slave trade and then slavery around the world. For over a century, Britain stood at the forefront of the push to end both, using much effort, losing many lives, spending much money, and exerting much diplomatic pressure to achieve these goals. Yet, you would not know it today from the narrative from campaigners and activists keen to denigrate Britain’s history and to destroy our sense of identity in and through it.

In February 2021, Jeremy Clarkson launched a tirade in the Sunday Times. Uninterested in any lesson that activists might have to teach about Britain’s past, he declared, the ‘history lesson that floats my boat’ is ‘the stories of British slave rescues we never hear about’. Clarkson continued, ‘I’ve been doing some research about the Royal Navy’s West Africa Squadron, which was formed in 1808, just a year after Britain abolished the slave trade. It was stationed at first in Portsmouth and equipped with two warships, and its job was to patrol the west coast of Africa, apprehending anyone who was ignoring the new law’, freeing ‘thousands of slaves’. He gave the example of the most famous ship in the squadron, the Black Joke, which had captured the Spanish brig El Almirante.

In the hold, the captain of the Black Joke — a man called Lieutenant Henry Downes — found 466 slaves, who were later landed and freed. This sounds like the sort of exciting story that would enliven a history lesson, but I’m afraid no one really knows anything about Downes. I suppose his story doesn’t tally with current thinking … I guess that muddle-headed lefties really don’t like the idea that for nearly a hundred years, and at vast expense, the country that they hate waged easily the most morally just war of all time.

Clarkson wanted to emphasise that Britain’s history was more about antislavery than slavery. He claimed that ‘the Royal Navy’s operations to end the slave trade cost more than Britain had earned from earlier slaving enterprises.’ Alex Renton wrote to the Sunday Times pointing out that this was untrue, but the paper dismissed Renton’s complaint. Only when Renton went through IPSO was the paper obliged to add, a year after the original publication, ‘We have been asked to point out that the consensus among historians is that this was not the case, and we are happy to set this on record.’ This was not the only aspect of Clarkson’s story that was incorrect, but a seed had been firmly planted. Celebrating the Royal Navy’s ‘liberation’ of captives was a way of countering the attention that Black Lives Matter had brought to bear on Britain’s involvement in slavery and the slave trade.

The Case for the Memorial

In August 2023, Wanjiru Njoya, author of works such as ‘Harry Frankfurt, Humbug, and the Battle against Wokery’, ‘The Socialist Road to Destruction amid So-Called Good Intentions’ and ‘Civilization Depends upon Economic Freedom’, posted a proposal on X (formerly Twitter) for a memorial ‘to honour the men of the Royal Navy West Africa Squadron’. In October 2023, Colin Kemp, a semi-retired management consultant from Chichester launched the West Africa Memorial Fund to raise the money for such a memorial in Portsmouth. In the course of conducing genealogical research Kemp had learnt that 1,587 British sailors had died to rescue ‘tens of thousands of people from a lifetime of servitude and torture’. A memorial he said, would ‘not only honour those who lost their lives but highlight Britain’s role in ending slavery’, it would also redress a situation in which ‘no one seems to know that we were the first country to abolish’ slavery.

There was already ‘a small part dedicated to the West Africa Squadron’ in The Royal Navy Museum, but Kemp insisted that ‘there needs to be something quite major.’ His initiative was for a ‘larger, free-standing memorial that would commemorate the facts that between 1807 and 1867, Royal Navy sailors ‘freed over 150,000 Africans who were going to become slaves in America’, by capturing 1,600 slave ships. He claimed that ‘during the height of the 1840s, the squadron took half of the naval budget and 2 per cent of the country’s GDP.’

Kemp’s aim was to raise £70,000 to commission Vincent Grey, who had designed the Horatio Nelson statue in Chichester. His campaign received a major boost when the Daily Mail took up the cause in October 2023. The paper added a new justification. The memorial was needed not just to celebrate the West Africa Squadron, but to demonstrate that ‘Britain has “very little to apologise for” over slavery’ itself. In the Mail’s reporting, the Squadron’s 1,587 casualties sky-rocketed to 17,000, the extra 15,000 being those who had died after succumbing to diseases and illness.

History Reclaimed’s Robert Tombs joins the campaign

Momentum was building. In January 2024, the Conservative Leader of the House of Commons and Portsmouth North MP Penny Mordaunt told the Daily Mail that, unless Kemp’s memorial is erected, the ‘truth is in danger of being lost forever’. She did not make clear why it is only truths memorialised in bronze that are remembered, but she did ‘hit out at “anti-British, grievance-based” attempts to rewrite history’. The memorial would make it clear that ‘the country is not to be ashamed of its past or keep quiet about the achievements of its armed forces … Yes, Britain had a role in the slave trade. Yes, people made money out of it. But let’s be clear about something. We ended it. Our biggest contribution to the evil trade was to end it. We should honour those who gave their lives fighting to do that.’

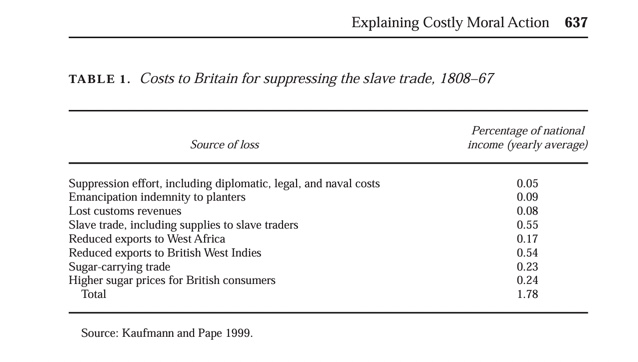

This Daily Mail piece was the first, but not the last, to include a quote from an article by Robert Pape and Chaim Kaufmann published in the little known academic journal International Organisation in 1999. They had apparently described the Royal Navy’s antislavery patrols as ‘the most expensive moral action in modern history’. That claim was important to the campaigners. It suggested that Britain as a nation made great sacrifices to end the slave trade, simply because it was the right thing to do. In this Daily Mail article, the ‘half of the Royal Navy’s budget’ that Kemp claimed had been spent on the West Africa squadron was allocated a figure: ‘equivalent to as much as £50 billion today’. Mordaunt stated that this was the amount of the entire defence budget. It was also no longer an individual proposing the memorial, but a group of ‘local historians’, while the campaign group had become a private limited company with a raised target figure of £100,000. When the Tory peer Lord Ashcroft donated £25,000, things were looking good for the campaigners.

In May 2024, however, the project received its first major setback. The campaigners had been in negotiation for a suitable location with Landsec, the company that owns Gunwharf Quays on Portsmouth Harbour’s edge, but before agreeing to release the site, Landsec had consulted with its ‘corporate affairs team and employee diaspora network.’ Having seen the design, they decided that ‘the proposed memorial lacked sensitivity and authenticity to what is a very emotive topic and dark part of our history as a nation’. The Daily Mail turned to Toby Young, founder of the Free Speech Union, who declared ‘Landsec’s decision to effectively toss the West Africa Squadron Memorial into the English Channel is outrageous.’ At this point the History Reclaimed founder and author of Colonialism: A Moral Reckoning, Nigel Biggar, weighed in, writing for the Mail that

Landsec is afraid of looking racist, though it is apparently not concerned about revealing its utter ignorance of history. Presumably, the “diaspora” refers to people of African descent. Some of them may be the distant descendants of slaves. But they might also include descendants of those African slavers — and the traders who dragged their fellow Africans to the coast for sale to Europeans — as they had been doing for centuries, first to the Romans and then to the Arabs. So why on earth would they or anyone else regard a statue as “non-inclusive” and “insensitive” for commemorating the Royal Navy’s heroic anti-slavery West Africa Squadron? Why would they not want this important, admirable part of the truth about Britain’s history remembered? The obvious reason is that it’s a story of white Britons doing good to black Africans. As such it distracts from the Black Lives Matter-inspired mission to keep our focus absolutely fixed on the evils of African enslavement and on British guilt for it. Any celebration of how Britain fought against the slave trade disturbs the politically advantageous, comic-book narrative of unremitting black victimhood at the hands of white oppressors.

Like Clarkson, Biggar extolled the heroism of HMS Black Joke. He also followed the TV celebrity by weighing up the costs of antislavery against the profits from the slave trade, only with a little more sophistication. Biggar took the time to track down the academic source that Clarkson had bowdlerised after receiving it second or third hand. Rather than directly repeating the erroneous claim that ‘the Royal Navy’s operations to end the slave trade cost more than Britain had earned from earlier slaving enterprises’, Biggar selected an extract from the historian of slavery David Eltis’ more circumspect words: ‘The British spent almost as much attempting to suppress the trade between 1816 and 1862 as they received in profits over the same length of time leading up to 1807’. We will return to Eltis’ calculations and the context in which he was careful to place them below.

Biggar followed Penny Mordaunt too, citing Kaufmann and Pape’s conclusion ‘that Britain’s effort to suppress the Atlantic slave trade was ‘the most expensive example [of costly international moral action] recorded in modern history’. He elaborated: while ‘some would argue there was an obvious commercial advantage to Britain in disrupting our European rivals’ slave trade, Kaufmann and Pape had ‘found the real driving force was not economic but religious: in the churchgoing 19th century, moral duty counted for more than any financial incentive. The British were among the first people in history to repudiate and abolish slave-trading and slavery — at colossal cost in money, diplomatic effort, naval resources and lives.’ Biggar’s conclusion was, ‘Rather than kowtow to the distorted, biased agenda of the BLM movement, imported from the U.S., Landsec should try to copy the moral courage of HMS Black Joke’s heroic sailors — and salute one of the noblest episodes in our national history’.

The Case Against the Memorial

There are four main reasons for objecting to this memorial: the campaigners’ motives, their misrepresentation of history, their obfuscation about the fate of those supposedly ‘freed’ by the Squadron, and the proposed design.

1. Motives

We don’t have to assume the memorial campaigners’ motives because they have been quite explicit. They want to deflect the spotlight that Black Lives Matter has directed at Britain’s extensive participation in the slave trade and the Atlantic system of slavery. Dismissing antiracist campaigners’ grievances as merely historic, they are also denying that racism is still a significant issue. In the campaigners’ view, antiracists are simply ‘muddle headed lefties’ who ‘hate Britain’ and Black Lives Matter is an ‘anti-British, grievance-based attempt to rewrite history.’ The Daily Mail is campaigning for the memorial to demonstrate both that ‘Britain has very little to apologise for’ over slavery and no significant contemporary racism to concede.

According to Office for National Statistics figures, let alone a barrage of other forms of evidence, Britain still has a significant issue with racism whatever the memorial campaigners might say. Black Lives Matter’s ‘grievances’ were not concocted and neither were they ‘anti-British’. When Colston’s statue was toppled, the mortality rate from COVID was running at 256 per 100,000 Black men and only 87 per 100,000 White men. Black women were dying at the rate of 120 per 100,000 and White women at 52 per 100,000. The discrepancies were due to the over-representation of Black people in low-paid public-facing service roles, along with housing and health inequalities. In 2016 black graduates were paid 23 per cent less than their White counterparts, and since 2010 there had been a 49 per cent increase in the number of unemployed ethnic minority sixteen to twenty-four years olds, while the figure for their white counterparts had fallen by 2 per cent.

Black people were twice as likely to be murdered and, when accused of crimes, three times more likely to be prosecuted and sentenced than White people. In 2022, Black households were the most likely out of all ethnic groups to have a weekly income of less than £400. People in White British households were consistently the least likely to live in low-income households. In every region in England and in Scotland, unemployment rates are lower for White people than for all other ethnic groups combined, with the biggest differences in West Midlands, the North- East and Yorkshire and the Humber.

The Windrush scandal was part of the British social fabric that gave rise to the 2020 protests. As the official report explained, it was allowed to happen in part ‘because of the public’s and officials’ poor understanding of Britain’s colonial history, the history of inward and outward migration, and the history of Black Britons’. The dumping of Edward Colston’s statue in Bristol Harbour reflected these facts. As David Olusoga explains, ‘Those wrongly caught in the dragnet of the hostile environment were the children of men and women who had been encouraged to migrate to post-war Britain … These people with their centuries’ long links to Britain and British history, were suddenly classified as illegal immigrants in the country they had called home for decades … The Colston statue, like hundreds of others scattered across Britain, was … an active part of the great amnesia and obfuscation that has long functioned to airbrush the realities of slavery and the slave trade out of the mainstream of British history’. He continues,

… the generation that found its voice and expressed its demands in the summer of 2020 not only had access to a once-hidden history, they came to it with attitudes radically different from those of their parents’ and grandparents’ generations. Rather than being eager to conceal and whitewash over the inglorious and murderous chapters in the long history of Britain’s relationship with Africans and Africa they were determined to confront them. The historical amnesia that enabled the veneration of slave-traders and empire-builders is to them a clear and obvious outrage. This determination to acknowledge and confront Black British history and draw it into the mainstream is new and may well shape our relationship with our national history in the coming decades.[1]

The West Africa Squadron memorial initiative is driven by the powerful political backlash against any such reshaping. Its intention is to restore and preserve a conventional, White-Centred, celebratory history of Britain. The sailors who lost their lives off the West African coast are merely incidental to it.

2. Falsifying History

Penny Mordaunt tells us that ‘… there’s a new generation having its first encounter with historic facts. It’s important that they are told the truth’. But she and the other campaigners have told a number of untruths.

Whereas Kemp and the Mail have claimed that ‘we were the first country to abolish’ the slave trade, Denmark abolished its slave trade in 1802, followed by Great Britain and the United States in 1807. Britain was not the first country to abolish slavery itself, as Kemp claimed in the Mail, either. That was Haiti. Furthermore the campaigners have consistently distorted the history of the Royal Navy’s antislavery initiative by misrepresenting its financial costs, cherry picking the academic literature on it and obscuring the fate of those supposedly ‘freed’.

To return now to Biggar’s reckoning of the financial costs and benefits of the slave trade. He was more accurate than Clarkson, but there was still manipulation involved. The selection of Eltis’ words used by Biggar was ‘The British spent almost as much attempting to suppress the trade between 1816 and 1862 as they received in profits over the same length of time leading up to 1807.’ However, Biggar omitted the start of this sentence. It began, ‘In absolute terms, the British spent almost as much …’. This is significant because, as Eltis went on to explain, in the forty-six year period leading up to 1807, the money generated from the slave trade was a larger proportion of National Income than the money spent on antislavery during the succeeding period. Furthermore, Britons had made money from the slave trade not just for the forty-six years leading up to 1807, but for some 200 years. The profits made from trading in captives over this extended period vastly outweighed the costs of the Royal Navy’s suppression at the trade’s end.[2]

The memorial campaigners have also inflated the costs of the West Africa Squadron. They claim repeatedly that ‘the squadron took half of the naval budget and 2 per cent of the country’s GDP.’ This is not true. The figure is based on the table below from the oft-cited Kaufmann and Pape article. The campaigners have rounded up the grand total at the foot of the table as the costs of the West Africa Squadron alone. But this figure of 1.78 per cent of National Income includes the cost of compensating slave owners for the loss of their enslaved ‘property’ after emancipation in 1834. This amounted to £20m, equivalent to 40 per cent of annual government revenue. The table also includes the projected opportunity costs of earnings from both the slave trade and slave ownership, had they been allowed to continue. These account for the customs revenue, trade, exports and sugar carrying trade rows. The final row is the counterfactual price increase for sugar that British consumers are presumed to have paid as a result of the abolition of slavery after 1834. None of these rows have anything to do with the costs of the West Africa Squadron. The only row that does is the first and smallest figure, accounting for 0.05 per cent of annual National Income, or one fortieth of the claimed ‘half of the naval budget and 2 per cent of the country’s GDP’.

A more realistic assessment of the scale of the squadron and its achievements is given by the same David Eltis whom Biggar cited selectively on its costs. Eltis concluded that the squadron

usually absorbed a small proportion of British naval strength and was sensitive, first, to competing demands on naval resources and, second, to the possibilities of success … Immediately after 1815 when the British had lost the wartime right to search vessels and before the 1817 conventions with Spain and Portugal came into effect, the West African squadron was close to the size necessary to protect British trade, and no more. It was doubled in the year the courts of mixed commission were opened [see below] and increased a further 50 percent with the formal abolition of the Cuban trade. Thereafter it changed little until the Anglo-French conventions of 1831 and 1833 and the concomitant formal abolition of the Brazilian trade. These measures effectively opened up the traffic south of the equator to British interference … The ending of the Brazilian traffic in 1851 saw a diminution of the squadron’s strength. But the major weakening of the force occurred in response to armed conflict elsewhere. The sharp drop in 1840 occurred at the time the first naval expedition in the Opium War was being assembled as well as the period of strained relations with France. The Crimean War is also clearly apparent … [in its effects] for the years 1854 to 1856. At the peak of the British antislave-trade effort, in the mid-1840s, about 15 percent of British warships in commission and nearly 10 percent of total naval manpower were assigned to the task of interrupting the flow of coerced labor to the Americas.

The British had the biggest but not the only antislavery squadron, since the French, Americans and, to a lesser extent Portuguese and Brazilians also joined in at various points. The French antislavery squadron ‘was doubled to twenty-eight as a consequence of the Anglo-French convention of 1845 and at this point was absorbing one fifth of French naval resources’. Overall, Eltis’ claim was that British naval suppression did very little to eliminate the slave trade. The West Africa squadron was hardly effective before 1850, and even after that, only because of Brazilian and Cuban withdrawal from the trade.

Returning to the Kaufmann and Pape paper, we can recall the memorial campaigners’ repeated quote referring to the West Africa Squadron as ‘the most expensive example [of costly international moral action] recorded in modern history’. From this Biggar inferred that ‘The British were among the first people in history to repudiate and abolish slave-trading and slavery — at colossal cost in money, diplomatic effort, naval resources and lives’, because of their moral and religious conviction. In fact Kaufmann and Pape interpreted the decision to enforce abolition as being ‘a function of three factors’:

First, the political needs of the ruling elite. The more precarious their hold on power and the more intense their fear of losing power, the greater their incentive to bargain [with lobbying groups such as the antislavery activists]. Second, the enhanced political legitimacy that the rulers can gain from association with the saints and their program … Third, the extent to which the saintly faction can ally with more than one main political faction. Moral movements whose supporters’ positions on other issues lie near the middle of the political spectrum will have greater leverage than those whose loyalties are confined to one end.

For all their invocation by the campaigners, Kaufmann and Pape reached the same conclusion that the Nigerian-American historian Moses Nwulia had reached in 1975 – that British antislavery intervention was ‘more the humanitarianism of self-interest than anything else’.[3] The treaties that Britain negotiated with African rulers to end the slave trade reflected this pursuit of more self-interested goals. Whilst insisting on ending the sale of captives they also obliged kingdoms to grant a most-favored-nation status for British commerce, protection for British property and freedom for Britons to trade with any individual or group within the African territory. But, as Eltis explains, ‘the resistance of Africans to such broad terms, particularly the last, meant that the standard slave trade treaty quickly came to encompass only the first two of the above provisions’.

For all of Penny Mordaunt’s insistence on historical truth, the memorial campaigners have distorted the findings of every academic source they cite to suggest British moral purity.

3. The Myth of Liberation

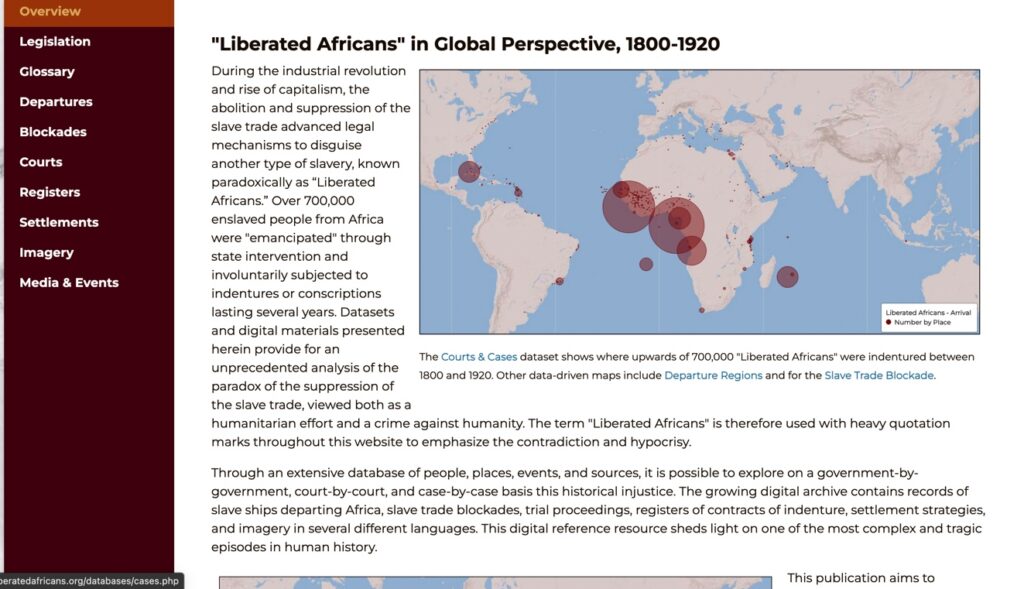

Perhaps the campaigners’ slyest manoeuvre is obfuscation about the fate of the captives supposedly ‘liberated’ by the West Africa Squadron. They repeatedly state that once taken aboard Royal Navy ships these enslaved people were, in Clarkson’s words, ‘landed and freed’. They were not. They were ‘disposed’ of in accordance with British imperial requirements.

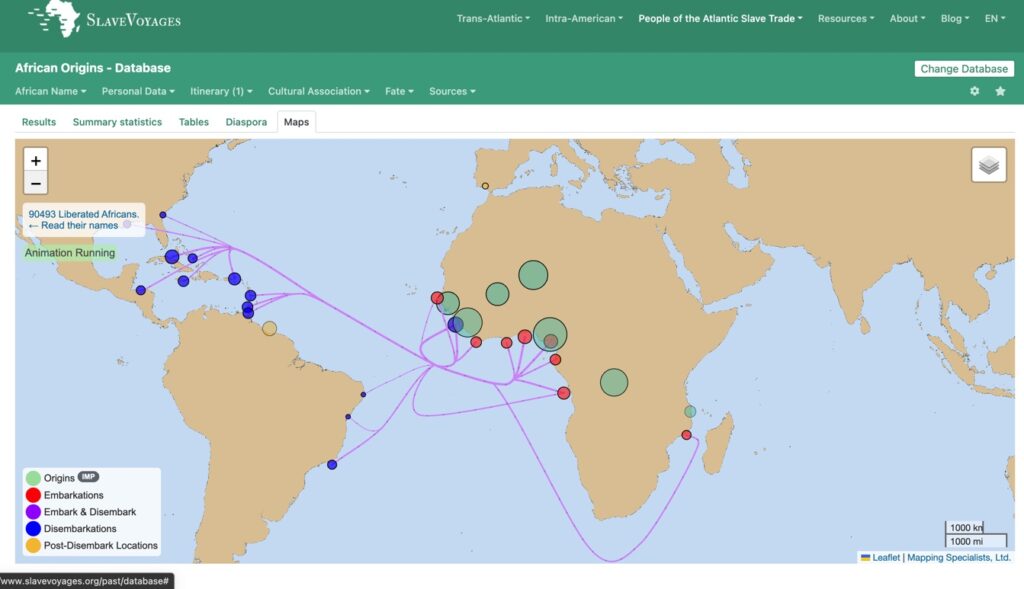

While many of the Royal Navy’s officers and crew showed genuine compassion and goodwill towards the captives taken on board, these people were only technically released from slavery. They continued to be treated as disposable units of Black labour. The historian Richard Anderson has written an excellent summary of the large and ever-growing body of literature outlining their varied fates, from which much of the following description is drawn.[4]

From 1808, when the West Africa squadron was established, until 1834, when slavery was abolished, captives found aboard the ships intercepted by the squadron remained the property of the Crown. A clause in the 1807 Act abolishing the slave trade and establishing the squadron required that they be enlisted, apprenticed, or ‘disposed of.’ Enlistment meant the forcible recruitment of at least 8,000 people into the West India Regiments, Royal African Corps, and Royal Navy. Those not enlisted, including the women and the children, who amounted to forty per cent of ‘liberated’ Africans, were ‘disposed’ of as ‘apprentices’, bound to unpaid work for colonists and colonial governments ‘for any Term not exceeding Fourteen Years’. Since they would be unlikely to choose such service unless forced, the Act allowed third parties to agree to indentures on their behalf.

https://liberatedafricans.org/about/essays.php

Special Courts of Commission were established in Sierra Leone, Cuba, Rio de Janeiro, Tortola, Cape Town, St. Helena, Angola and Mauritius to act as this ‘third party’, overseeing the indenture process. The Liberated African project based at the University of Colorado is trying to recover the ‘identity of each child, woman, or man documented by name’ in their proceedings. Corruption was rife, with court officials assigning the captives they most desired to their own homes, plantations and farms. Female apprentices were regularly coerced into sexual relationships with their allocated masters.

The West Africa Squadron’s sailors were often deeply affected by the conditions in which they found captives aboard seized ships. But its is likely that some would have served on slave ships before entering the Royal Navy’s service and they received a share of the ‘prize’ value of any slave-trading vessel they captured, just as they did for the capture of enemy ships. The value of the ‘cargo’ of captive people contributed to this prize, with ‘headmoney’ earned for each captive. One of the squadron’s sailors, John M’Kie, wrote in his memoirs that the ‘capture of a full slaver had a very exhilarating effect … the chief talk being how much prize money it would bring’, although the rewards were often disappointing once condemned ships’ value – around £1 million between 1807 and 1846 – had been parcelled out unevenly among the crew. The intercepted slave ships were taken by a ‘prize crew’ not to the nearest African coastline as one would assume from the campaigners’ propaganda, but to the nearest ‘disposal’ court. They often endured a voyage of months and mortality rates that differed little from those of the ‘middle passage’ from which they were saved.

https://www.slavevoyages.org/past/database#maps

In Sierra Leone, the ‘liberated’ Africans were initially sold to colonists from a cattle pen. In the longer term, at least 75,000 were allocated to masters and mistresses as menial agricultural labourers or household servants, many of the children being handed over to missionaries to look after. Some were able to assimilate into Sierra Leonean society and attain a relatively high status. The most notable was Samuel Ajayi Crowther, who became the first Anglican Bishop of West Africa. However, adverts were issued for the recapture of others who absconded from their indentures, in the same way as they were for runaway slaves. In the Caribbean, Mauritius and the Cape Colony adults were put to work alongside or instead of enslaved people on plantations and farms, while children were ‘disposed of’ as personal servants. After the abolition of slavery in 1834, former slave owners were assigned ‘liberated’ Africans, along with indentured Indian workers, to address the shortage in labour supply. In Brazil and Cuba, they were bought, sold, and traded like enslaved people. Many had their terms of apprenticeship extended by years and even decades.

The ‘disposal’ of these supposedly ‘freed’ people was not the end of the story. They remained subject to constraints that were inconceivable for free White subjects, including further involuntary relocation. From 1818 onward, approximately 3,500 were forcibly transported from Sierra Leone to British settlements along the Gambia. Some 15,000 were later transported to the West Indies to cover the labour shortage caused by emancipation. This was a majority of those ‘liberated’ by the West Africa Squadron after 1848. Most of the ‘liberated’ Africans taken to St. Helena were moved on again. The overwhelming majority of the 18,000 survivors from the 24,000 people taken to the receiving ‘depot’ were forcibly shipped to Caribbean colonies or the Cape Colony, some of them in terror of the fate that awaited them. None was returned to their African homeland.

Despite some remarkable stories of a few among the ‘liberated’ Africans absconding and even pooling resources to buy ships to secure their own freedom, Anderson’s conclusion, and that of a great number of historians in a great many publications, is that ‘Liberated African migration was a morally ambivalent program of forced labor and relocation’. Those ‘rescued’ and ‘freed’ by the West Africa Squadron are often described by specialist historians not as ‘liberated Africans’, but as ‘Recaptives’. Long after the trans-Atlantic slave trade had ended and slavery had been abolished by the European colonial powers, Black people, including these ‘Recaptives’ continued to be treated as disposable units of labour. As Nancy Stepan put it, ‘just as the battle against slavery was being won by abolitionists, the war against racism in European thought was being lost’.

It is inconceivable that the memorial campaigners are unaware of all this. Their casual assertion that the Squadron ‘freed’ captives without any further information about their ensuing fate suggests a knowing and dishonest elision. To have recounted that fate would have been to undermine the White ‘virtue signalling’ upon which the memorial campaign relies.

4. The Memorial Design

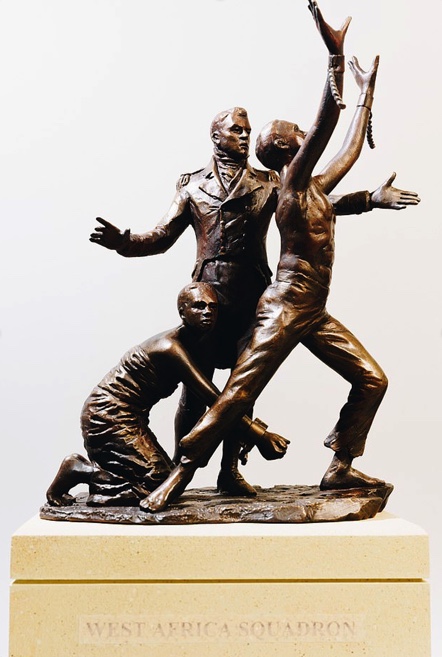

Given the fate of ‘liberated’ Africans, anyone with the slightest sensitivity might appreciate why Landsec’s employees felt that the proposed memorial design (see below), lacks sensitivity and authenticity. It could not manifest the White Saviour complex more explicitly if it tried.

The Proposed Memorial

One of the squadron’s vessels that has been studied in detail, HMS Waterwitch, provides an example of the racially mixed nature of the squadron’s crews. During the initial months of a three year cruise at the peak of the Squadron’s activities in the early 1840s, it captured 29 slave ships and a number of boats as well as ‘freeing’ 877 captives from raiding barracoons on shore. Its captain, Henry Matson, knew that such work was impossible without the help of African sailors with experience of the coast and its ‘trade’. In the early months of the cruise he took on 20 of these men, known as Kru, mostly at Sierra Leone. Roughly a third of the ship’s crew at any one time was Black. Matson described them ‘to the parliamentary select committee as “the most serviceable” people on the squadron, who it was impossible to do without’. However, all of the Kru were discharged from the vessel while it was still in the South Atlantic so it is unlikely that they collected the considerable prize money from the cruise which was awarded to the rest of the crew. Not one African is listed on the memorial column to the Waterwitch in Jamestown’s Castle Gardens.

Eclipsing Africans’ role in the ‘liberation’ of other Africans all over again, the proposed memorial shows a single White British officer guiding two enslaved Africans to freedom. The captive woman is still in shackles and supine while the man is breaking his chains as he arises. The design is not only based on the lie of ensuing freedom, but is also racially infantilising and patronising.

Biggar wondered in the Daily Mail ‘why on earth … they [Landsec] or anyone else’ would regard this memorial ‘as “non-inclusive” and “insensitive”’’. I think the answer is pretty obvious. In fact he gave it himself: it’s nothing more than ‘a story of white Britons doing good to black Africans’.

*With thanks to Andrew Pearson, whose Distant Freedom: St Helena and the Abolition of the Slave Trade, 1840-1872, Liverpool University Press, 2016 is the best source on St Helena.

[1] David Olusoga, Black and British: A Forgotten History, revised ed. Picador, 2021, 530-334.

[2] David Eltis, Economic Growth and the Ending of the Transatlantic Slave Trade, Oxford University Press, 1987, 97.

[3] Moses D. E. Nwulia, Britain and Slavery in East Africa, Three Continents Press, 1975.

[4] Richard Anderson, Liberated Africans, Oxford Research Encyclopedia of African History, 2021, Retrieved 27 Jun. 2024, from https://oxfordre.com/africanhistory/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190277734.001.0001/acrefore-9780190277734-e-741.

The Right Wing Culture War and the Refusal to Listen – Alan Lester

[…] policies. This memorial idea has been politicised from the first, however. It is associated with a campaign by the Daily Mail and Penny Mordaunt to deflect from the attention that slavery has been getting in the wake of the Black Lives Matter […]